The science behind a human cause for observed climate change is unequivocal, and the technology, data, and statistical modeling methods needed to confirm that is readily available to anyone, he notes. The emphasis now is on quantifying and assessing the global impact: political, economic, and human.

For many years, Wehner and his colleagues have focused on studying the behavior of extreme weather events in a changing climate, with particular emphasis on heat waves, intense precipitation, drought, and tropical cyclones. In the last decade, however, they’ve begun to look at the role of “extreme event attribution” (EEA) – that is, the study of to what extent, if any, human influence has contributed to individual extreme climate and weather events, and what the long-term effects of this might be on populations around the world.

In a comment piece published November 16 in Nature Climate Change, Wehner and his co-authors looked at the top four classes of deadly extreme weather events worldwide in the context of EEA modeling and the development of “loss and damage” mechanisms (ways to support developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change). Among other things, the researchers concluded that EEA techniques can substantially help inform negotiations about financial allocations to impacted vulnerable countries for the most damaging extreme events.

“What prompted this paper was a recent editorial piece that suggested that EEA is not ready for the loss and damages discussion. But we feel there is a naivete to that position,” Wehner says. “Our role as scientists is not to make policy decisions but rather to provide the best information we can to the people who are indeed responsible for such political decisions.”

Addressing Loss and Damages

The last few years have kept Wehner busy in his efforts (along with many collaborators and colleagues) to bring more attention to EEA research and what it means for addressing the impact of extreme weather events worldwide. In addition to the Nature Climate Change paper, he authored an article in Physics Today (September 2023) in which he stated, “Using extreme event attribution techniques, it is now possible to make quantitative statements about the human influence on many classes of individual weather and climate events.”

He is also co-author of several related papers, including “Real-time attribution of the influence of climate change on extreme weather events: a storyline case study of Hurricane Ian rainfall” (2023) and “Attribution of 2020 hurricane season extreme rainfall to human-induced climate change” (2022); and lead author on “Operational extreme weather event attribution can quantify climate change loss and damages” (2022).

In parallel with these research activities, Wehner was invited to testify in Washington, D.C., before the U.S. Senate Environment and Public Works Committee on November 1 on “The Science of Extreme Event Attribution: How Climate Change is Fueling Severe Weather Events.”

Michael Wehner testifying about extreme event attribution before the U.S. Senate Environment and Public Works Committee on November 1, 2023.

“Extreme weather attribution science attempts to quantify the influence of climate change on specific individual events by answering two related questions,” he told the committee. As complex events have complex sets of causes rather than one single cause, attribution scientists do not make statements like “climate change caused this heat wave,” but rather focus on two related questions, borrowing methods from epidemiology: “First, has global warming affected the severity of an event of a particular frequency (say, once in a century)? And second, given the observed magnitude of intensity of an event, has global warming affected its rarity?”

The key to answering these questions, he added, “is for scientists to use both climate and statistical models to compare representations of weather events in the actual ‘world that was’ to a counterfactual ‘world that might have been’ without climate change.”

Wehner was also involved in the 5th National Climate Assessment (NCA) report released on November 14; his contributions included co-authoring the chapter on “Earth Systems Processes.” This being his fourth NCA report, he says he noticed a shift in emphasis in the findings compared to previous years – something he thinks the climate change community and others are ready for.

“The key climate science messages are pretty much the same, but this NCA report is more complete in terms of impacts,” he says. “The science of climate change takes up only two chapters, while the rest of the chapters focus on ‘what is this doing to us.’ That is what this latest NCA is about: the impact of climate change rather than the science itself, because we know the science pretty well.”

Toward Environmental Justice

Wehner also contributed to the 6th Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as co-author on the chapter “Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate”; a synthesis report of the 6th IPCC document was released in March 2023. Like the NCA report, the IPCC is expanding beyond demonstrating and quantifying the realities of human influence on extreme weather to finding ways to better analyze, understand, and address the impact and socioeconomic outcomes.

“The Synthesis Report brings into sharp focus the losses and damages we are already experiencing and will continue into the future, hitting the most vulnerable people and ecosystems especially hard,” the IPCC notes in an accompanying press release.

Both of these reports, along with Wehner’s testimony before Congress and a growing body of research on this topic, have helped bring another critical element to the forefront: new ways to address the issue of loss and damages. For example, at the 2022 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Conference of Parties (COP27), the global climate community discussed establishing a “loss and damages” fund to aid countries “particularly vulnerable” to the impacts of climate change. At the COP28 conference, taking place November 30 through December 12 in Dubai, this fund is expected to once again be a highly debated topic.

As EEA has taken on more of a role in these discussions, “the idea of a loss and damage fund has gained momentum as a way to provide funding for climate change impacts experienced in vulnerable countries,” Wehner and his co-authors write in the recent Nature Climate Change paper. “We argue that much of the information available from extreme event attribution, although far from perfect, can already substantially inform loss and damage activities.”

The takeaway, he adds, is that “As the Loss and Damage fund will be a topic of intense political debate at this month’s COP28 in Dubai, we feel the need to inform negotiators now that the science of EEA is solid, and if we are asked to do these kinds of calculations to support loss and damage negotiations, we have the technology. We’ve spent 20 years developing these methods, and they are ready. So even if we don’t necessarily have the human resources right now, we have the methods and the machines.”

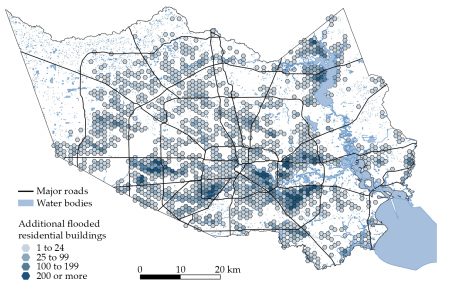

One of the things that motivates him and his colleagues in all of this is trying to quantify the environmental injustice of extreme weather events. “We’ve really only done this ‘end to end’ attribution once, with Hurricane Harvey, where our studies found that a degree Centigrade of human-induced warming in the Gulf caused 19% more rain, which caused 14% more flooded area, which caused 32% more homes to be flooded. And it turns out that those flooded homes were disproportionately low-income/Hispanic households. So these people were disproportionately affected. We are arguing that environmental injustice can be quantified and is exacerbated by climate change. Loss and damage proposals are, in essence, trying to address environmental injustice on a macroeconomic scale.”

Wehner emphasizes that moving forward with efforts to address the socioeconomic impact of climate change will increasingly require cross-collaboration among scientists, epidemiologists, public health specialists, and social scientists – and to strengthen the communication between these communities in developed and underdeveloped countries as well.

“This whole attribution thing is what I call an exercise in causality or causal inference,” he says. “That is where our team’s statistical expertise comes in, but there is still work to be done. In order to really make this work, scientists in developed nations need to engage with scientists in developing nations because they understand – whether they be physical scientists or social scientists – the reality on the ground better than I ever can.”

About Computing Sciences at Berkeley Lab

High performance computing plays a critical role in scientific discovery. Researchers increasingly rely on advances in computer science, mathematics, computational science, data science, and large-scale computing and networking to increase our understanding of ourselves, our planet, and our universe. Berkeley Lab's Computing Sciences Area researches, develops, and deploys new foundations, tools, and technologies to meet these needs and to advance research across a broad range of scientific disciplines.