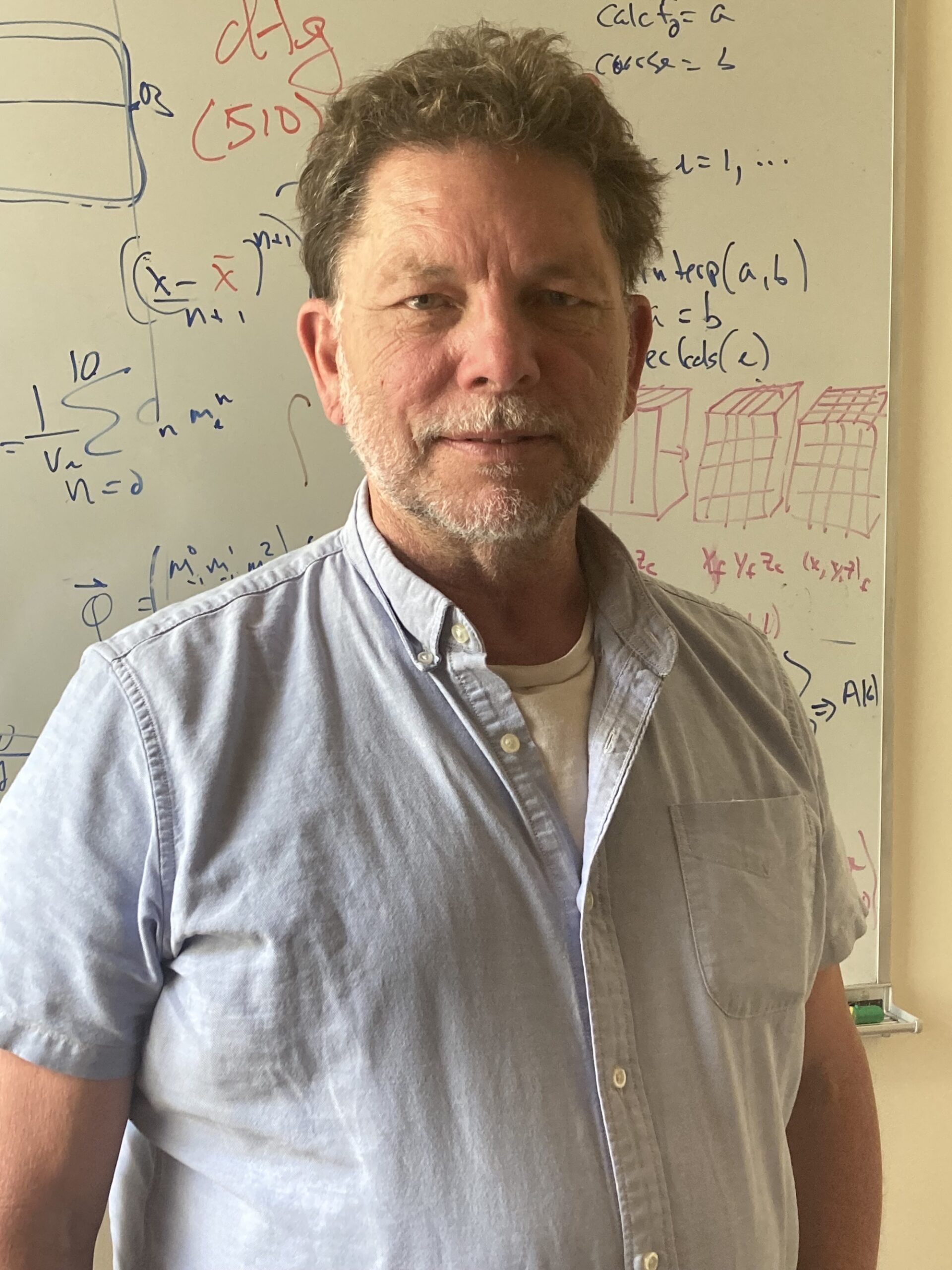

Peter Schwartz

For Peter Schwartz, a research scientist who joined the Computing Sciences Area’s Applied Numerical Algorithms Group (ANAG) in 2001, math has long been a pathway. Now, after 20+ years at Berkeley Lab, Schwartz is moving on – although he’s not exactly sure what he’ll be doing next.

While his training was in pure math, he pivoted some years back to scientific computing, particularly for environmental projects.

“When you have a degree in math, outside of teaching, the most obvious jobs are something related to defense or advertising or maybe the financial industry,” said the Berkeley native, who earned his undergraduate degree at UC Berkeley, followed by a Ph.D. at Ohio State and a postdoc at the University of Toronto. “I was lucky that I could work in science.”

So in the late 1990s, he decided to shift direction, embarking on a master’s degree at UC Davis where he could learn about climate science and pick up some computer skills in the process. When the opportunity to join Phil Collela’s group at Berkeley Lab came along, he was able to leverage his math background to learn about scientific computing. Family played an important part in the decision too.

“I knew it was time to come back to Berkeley,” he said, noting that, at the time, his son was young, and his mom was in her 70s. “Work/life balance has always been a very important part of this job for me; they are generous about letting me be a good family person. When my son was young, I wasn’t far from home, and now my mom is 98 and needs assistance, and there’s been a lot of allowance for that.”

Surface Water in California

For Schwartz, the most interesting project at the lab was working with the California Department of Water Resources to develop a model of the San Francisco Bay and Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

The surface water model of the Bay and Delta grew out of a response to state-based water management concerns ranging from the increased demand for water, pollution from agricultural run-off, and danger from levee breaks and island flooding. Starting in about 2010, through a contract with the state of California, Schwartz and his ANAG colleagues used adaptive mesh refinement and computational fluid dynamics to create a two-dimensional shallow water model that simulated flows in the Bay and Delta. That project provided funding and excitement for a number of years.

“Part of the surface water project was an interesting mathematical algorithm that involved incorporating the information from digital elevation maps, maps that show topography and bathymetry, into the equations that model the flow of water,” Schwartz said.

Scientific computation across many applications relies on a common core of mathematics and algorithms. Schwartz worked tangentially on systems biology, fusion energy, general relativity, and environmental flows like atmosphere, water, and ice. “The math and the algorithms provide the opportunity for someone like me with little scientific training to interact with interesting, well-trained people in lots of different areas,” he said. For example, the algorithm and software that incorporated digital elevation maps for the project with the California Department of Water Resources has turned out to be useful in many other applications. In fact, a paper that appeared in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science – and which Schwartz considers the most interesting publication he has been involved in – used the same algorithm in a computation of surface diffusion in molecular biology.

Most recently, Schwartz worked with Dan Martin on E3SM, a climate model, and also on getting BISICLES, an ice-sheet model primarily created by Martin, to work with E3SM. The goal was to improve the ice sheet modeling inside the climate model.

“I’ve worked with smart people at Berkeley Lab. I wasn’t trained in computation or even software development when I arrived, so I had a lot to learn. Some key people helped me along the way, including Martin, Terry Ligocki, and Dan Graves; and of course, the ideas and the vision of the software library originated with the founder of the group, Phil Colella,” Schwartz noted. “So I am appreciative of my good teachers, and that Phil gave me a chance to be here.”

Looking ahead, Schwartz – who for many years has enjoyed walking to work along the fire trails of the Berkeley hills – muses that he might go in a different direction.

“When I was in high school, if anyone asked me what I was going to do after I graduated, I really didn’t know. One day, on a whim, I decided to say ‘architect,’ and everyone loved that idea. That plan lasted about six months until I learned that, unfortunately for me, architects need very neat handwriting,” he said. “So I don’t really know what will come next. However, recently, when people ask me about the future, I’ve been thinking maybe…architecture is a good idea.”

About Computing Sciences at Berkeley Lab

High performance computing plays a critical role in scientific discovery. Researchers increasingly rely on advances in computer science, mathematics, computational science, data science, and large-scale computing and networking to increase our understanding of ourselves, our planet, and our universe. Berkeley Lab's Computing Sciences Area researches, develops, and deploys new foundations, tools, and technologies to meet these needs and to advance research across a broad range of scientific disciplines.