Anyone can ask a popular AI tool to create a photo‑realistic image of a cat — but generating a scientifically valid microCT scan of a rock sediment, composite fiber, or plant root is an entirely different challenge. In science, images aren’t judged by how convincing they look to the human eye, but by whether they capture precise, quantitative details that reflect real‑world physics and biology at microscopic or even atomic scales.

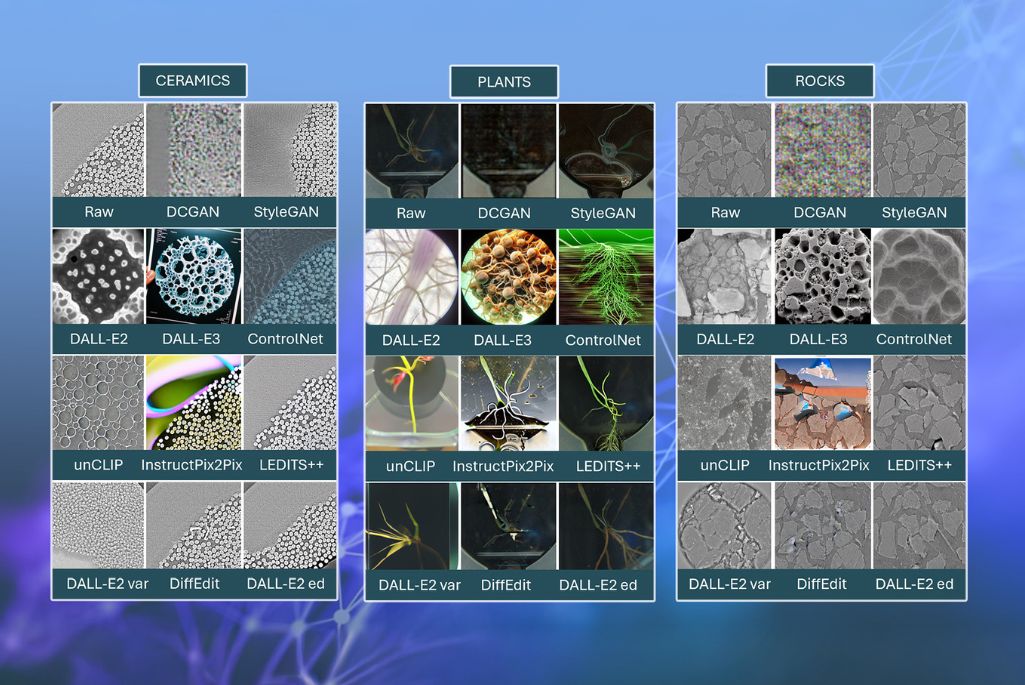

Now, researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have published one of the first in-depth evaluations of generative AI models for scientific imaging—a breakthrough that could help scientists fill critical data gaps, speed up analysis, and reveal patterns too rare or costly to capture through experiments alone. The study, published in the Journal of Imaging, compares how leading AI approaches — including Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), and Diffusion Models — perform in creating scientifically accurate images from datasets of high‑resolution images of rock sediments, composite fibers, and plant roots.

“When we generate images for science, we are not chasing aesthetics, we are chasing truth,” says Daniela Ushizima, a senior scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Applied Math and Computational Research (AMCR) Division and the principal investigator of this research project. “While consumer tools can dazzle with style, scientific models have to encode the real physics and biology. When the science is right, these models can reveal patterns we have never seen before and accelerate discovery in ways experiments alone never could.”

“Our work broadens the application of generative AI models to scientific imaging, moving beyond simple datasets like images of dogs, cats, and birds, which lack scientific relevance to our problems,” said Zineb Sordo, formerly a researcher in Berkeley Lab’s AMCR and lead author of the paper. “While some studies have applied generative AI to medical datasets, research on scientific images in other areas remains limited. Our goal was to evaluate how these models perform on images relevant to the Department of Energy National Labs. By systematically assessing their effectiveness with diverse scientific datasets—such as those related to materials science, plant roots, and rock samples—we provide valuable insights on how best to use these generative models in materials science and other fields, paving the way for broader adoption of these technologies in scientific research.”

By generating highly realistic and physically plausible images, these models not only fill critical data gaps and accelerate the pace of discovery, they also enable researchers to explore unprecedented scientific questions—such as uncovering new microstructural design rules or benchmarking algorithms at scale—by providing computer-based examples that reflect the real-world physics and structures critical for scientific breakthroughs.

Bridging Gaps in Scientific Imaging with Advanced Generative AI Techniques

In their paper, the team notes that different types of generative AI models have unique strengths in creating scientific images. GANs, particularly NVIDIA’s StyleGAN, excel at producing visually appealing and coherent images, consistent with biological and physical properties. In contrast, Diffusion Models, like OpenAI’s DALL-E 2, generate highly realistic images that are closely aligned with their intended meanings, although they sometimes struggle to maintain the necessary scientific accuracy while achieving that realism. The team also analyzed platforms like RunwayML and DeepAI and found that while these tools are helpful for creative image generation, they may not consistently produce scientifically accurate images suitable for rigorous research applications.

To reach these conclusions, the researchers conducted a thorough review and comparison of leading generative models. They evaluated these models using a combination of quantitative metrics—such as SSIM (Structural Similarity Index Measure), which assesses the structural similarity between two images; LPIPS (Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity), which measures perceptual similarity based image features learned by deep neural networks; FID (Fréchet Inception Distance), which compares the distributions of generated and real images; and CLIPScore, which evaluates how well generated images align with textual descriptions. These metrics assess image quality and similarity to real data, providing a comprehensive evaluation of the models’ performance.

The team then incorporated qualitative assessments from domain experts in materials science and biology. This multifaceted approach enabled them to evaluate the models’ overall performance and their practical applications in scientific contexts.

“Traditional quantitative metrics can tell us if an AI-generated image looks realistic or matches certain patterns in real data, but they can’t always detect subtle errors that make an image scientifically inaccurate. That’s why expert validation will remain essential for ensuring that AI-generated images meet the rigorous standards of scientific research,” said Ushizima, also a co-author of the paper.

To enable the comparison of these complex AI models, the team leveraged the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center’s (NERSC) Perlmutter supercomputer to generate results from pre‑trained models and to train others—like StyleGAN—from the ground up. By leveraging the system’s GPUs, they were able to process extensive datasets and conduct complex evaluations that traditional systems could not handle. This work not only enhances the efficiency and scalability of their research but also allows for deeper insights into the generative models and their applicability in scientific research.

By documenting their methodologies in detail — from the models and datasets used to the evaluation process — the team ensures transparency and reproducibility. Using standardized metrics such as SSIM, LPIPS, FID, and CLIPScore, they established a consistent framework for assessing image quality, strengthening the credibility of their findings and enabling other researchers to build on their work.

“Our systematic approach also allows us to effectively handle multimodal data, which refers to the integration of different types of information, such as descriptive text, images, and numerical data. While generative AI in healthcare research has largely focused on medical imaging—for example, combining scans with patient data to support diagnostic tasks—our research explores its potential in other fields. This emphasizes the need for domain-specific alignment of text and image models to achieve scientifically accurate multimodal image generation,” said Sordo.

“Because the large language models we used weren’t originally designed to process images and text together, a significant part of our work focused on giving precise prompts related to rock sediments and plant roots to bridge that gap. Looking ahead, we plan to enhance our models by integrating various types of data more effectively, which will help us generate even more accurate and relevant scientific images,” Sordo adds.

“The accuracy of some of these images is already quite impressive. Several of my colleagues and I have failed to select the real plant root images from the AI-generated images from ‘line-ups’ that Zineb Sordo and Daniela Ushizima have put together,” said Peter Andeer, a Research Scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Environmental Genomics and Systems Biology Division and a co-author on the paper.

With generative AI tools rapidly advancing, the Berkeley Lab team hopes their work will help scientists worldwide unlock new discoveries, bridge experimental gaps, and accelerate progress in fields such as battery research, energy storage, and advanced materials science. The researchers note that their achievements were made possible through collaboration with Berkeley Lab’s Center for Advanced Mathematics for Energy Research Applications (CAMERA), scientists from the Earth and Environmental Systems Area (EESA), and Biosciences researcher Trent Northen and his TWINS Ecosystem Project team.

In the coming years, the team plans to build on this work by developing approaches that tailor generative AI models for scientific imaging, enabling them to work with larger and more diverse datasets. They will also create robust validation and verification protocols to ensure that AI-generated images are both scientifically accurate and reproducible, meeting the rigorous standards required for research. These advances could help DOE researchers overcome experimental bottlenecks, reduce computational costs, and speed up discoveries in areas such as additive manufacturing, nanomaterials, and national security.

About Computing Sciences at Berkeley Lab

High performance computing plays a critical role in scientific discovery. Researchers increasingly rely on advances in computer science, mathematics, computational science, data science, and large-scale computing and networking to increase our understanding of ourselves, our planet, and our universe. Berkeley Lab's Computing Sciences Area researches, develops, and deploys new foundations, tools, and technologies to meet these needs and to advance research across a broad range of scientific disciplines.