This article originally appeared on the Exascale Computing Project website.

Long valued for their role in scientific discovery and in a variety of medical and industrial applications, particle accelerators have been used in many areas of fundamental research and credited with enabling Nobel Prize–winning research in physics and chemistry. But these high-end instruments also occupy a lot of space and carry hefty price tags. Even smaller accelerators, such as those used in medical centers for proton therapy, need large spaces to accommodate their hardware, power supplies, and radiation shielding.

Fortunately, over the last several years physicists, engineers, and computational scientists have been working to create more affordable and accessible particle accelerators by shrinking both the size and the cost while increasing the capability. One of the most exciting developments in these efforts is the plasma accelerator, which uses lasers or particle beams rather than radio-frequency waves to generate the accelerating field, allowing these devices to support accelerating-electric fields many orders of magnitude greater than conventional accelerators with a much smaller footprint – even able to fit on a tabletop.

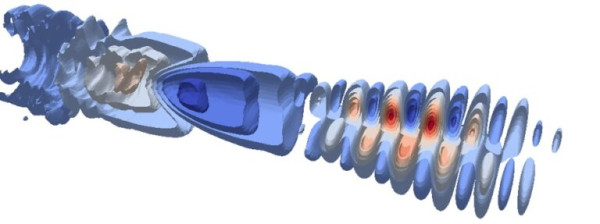

WarpX: longitudinal electric field in a laser-plasma accelerator rendered with the ECP software libraries Ascent & VTK-m as the simulation was running. Credit: Axel Huebl (Berkeley Lab)

The reduced size of plasma accelerators, however, presents challenges in controlling the intricate ultrafast processes at play, which are often on the picosecond and micrometer scales. Thus, realizing their compact designs requires novel mathematical and software capabilities to enable high-performance, high-fidelity modeling that can capture the full complexity of acceleration processes over a large range of space and timescales – simulations that are often computationally intensive. To address this issue, the WarpX project – a Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab)-led effort that also drew the attention and support of DOE’s Exascale Computing Project (ECP) – has spent the last six years creating a novel, highly parallel and highly optimized single-source simulation code for modeling plasma-based particle colliders on cutting-edge exascale supercomputers, with broad importance for other accelerators and related problems.

WarpX enables computational explorations of key physics questions in the transport and acceleration of particle beams in long chains of plasma channels, which could yield significant savings in the design and characterization of plasma-based colliders before they are built. Using exascale modeling to validate these devices could also lead to broader applications, such as sterilizing food or toxic waste, implanting ions in semiconductors, treating cancer, advancing fusion research, and developing new drugs.

“A lot of research still needs to be done and, like most things with plasma, you need big simulation tools because it’s complicated due to the large number of space and time scales. This is where WarpX comes into play,” said Jean-Luc Vay, a senior scientist at Berkeley Lab who heads the Lab’s Accelerator Modeling Program in the Applied Physics and Accelerator Technologies division and is PI for the WarpX project, leading the development of WarpX alongside co-PI Ann Almgren, also PI of the AMReX project. In addition to the Berkeley Lab core team, the ECP WarpX development team includes collaborators from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

Next-Generation PIC Solution

“The idea of WarpX is to provide a particle-in-cell (PIC) solution [a technique used to solve a class of plasma physics problems from first principles] that can tackle problems that are much bigger and faster than we could do before, allowing us to explore solutions for plasma acceleration at scales not previously possible,” Vay said. “We don’t need to do just simulations–we also need to study tolerances, which is highly computationally demanding. So we are pushing the state of the art with high performance computing.” In addition, since the PIC method is important for modeling many other beams and plasma physics problems, “the code is being designed to be generic and will advance solutions for a wide range of problems in accelerators, fusion, and more, far beyond the main focus on plasma-based colliders of the ECP WarpX project,” Vay added.

The original version of the code–dubbed simply “Warp” and developed by Alex Friedman and collaborators (including Vay and other WarpX developers) for DOE’s Fusion Energy Science program–used Fortran subroutines for fast number crunching that were wrapped in a Python top layer for simulations control and steering. While that version of the code incorporated many original, cutting-edge algorithms, like adaptive mesh refinement (AMR), it was not easily portable to run efficiently on both CPUs and GPUs; this hybrid architecture is a hallmark of emerging exascale supercomputers. As a result, “it became quickly clear that a full rewrite of the code using portable C++ primitives was the way to go for developing a single source code that runs efficiently on both platforms,” Vay said–a decision that led to one of the biggest challenges the WarpX team has faced so far.

So the team turned to AMReX, an ECP software library that provides a robust, efficient, and scalable implementation of AMR capabilities and versatile portable C++ primitives, which was developed by a team led by John Bell and Ann Almgren in the Applied Mathematics and Computational Research Division (AMCRD) at Berkeley Lab.

“AMReX is a numerical library that helps us implement physical block-structured mesh refinement algorithms on multiple computer architectures,” said Axel Huebl, a computational physicist and research software engineer in Berkeley Lab’s Accelerator Technology and Applied Physics Division and lead developer of WarpX. “Mesh refinement enables us to focus the computational power on the most interesting parts of a simulation, while staying effective for the larger, macroscopic evolution of, for instance, the plasma physics we model.”

Toward this end, as the WarpX team simulated longer chains of plasma accelerators at higher grid resolutions, the efficiency of the simulations was limited by the numerical limitations of the existing algorithms. So new algorithms were devised that removed some specific limitations, resulting in speedups of an order of magnitude or more in some cases. And after just one year of development, the AMReX team had the enhanced WarpX code up and running on GPUs, Vay said.

The ECP project has been an incredible boost to our scientific code developments and productivity. Many of us on the WarpX team agree that it has fostered, between WarpX, AMReX, and partners, the best collaboration experience that we have had to date in our scientific lives. In addition, ECP is enabling us to realize our vision of an integrated PIC ecosystem of codes that is part of a community of integrated scientific software. – Jean-Luc Vay (Berkeley Lab), WarpX principal investigator

“In addition to the question of what languages and programming tools we should use, we also had to change the way a lot of the algorithms are implemented,” said Andrew Myers, a computer systems engineer in AMCRD and a member of the WarpX team who has been instrumental in the AMReX implementation. “For example, we had to redesign the way a lot of the particle algorithms in AMReX work.”

“The AMReX team did an amazing job, doing a lot of tests to determine what the solutions could be and then developing this layer that provides a single source code that allows us to compile for CPUs or NVIDIA, AMD, or Intel GPUs,” Vay said.

Four Supercomputers, a Gordon Bell Prize, and More

With support from ECP and team members’ respective institutions, these development efforts are already paying off. In simulations run in 2022, the WarpX project demonstrated a 500x improvement in performance on the exascale supercomputer Frontier over the preceding version of Warp and was the first ECP application to reach its project goal by running at scale on Frontier. It was also the first code to perform 3D simulations of laser-matter interactions on Frontier, Fugaku, and Summit–something that has so far been out of reach for standard codes.

“With WarpX we can take the same code base and compile it for all of those different machines without having to make any changes to the code, and that was a big focus point of the effort and the project,” Myers said.

“That is something that ECP really puts an emphasis on,” Huebl added. “If you are working for such a long time on a project, how do you make this development sustainable? Our codes outlive the machines most of the time, so we intentionally plan it in a way that we can continue in five years when the next machine is coming along, and we don’t have to start from scratch and can optimize the code without having to rewrite everything.”

Another key milestone for the WarpX project was the successful implementation and deployment of the code for first-of-kind mesh-refined massively parallel 3D PIC simulations of kinetic plasma optimized on 4 of the 10 fastest supercomputers in the world (Frontier, Fugaku, Summit, and Perlmutter). This accomplishment earned the WarpX development team and collaborators from France and Japan the Association for Computing Machinery’s prestigious Gordon Bell Prize in 2022.

And the WarpX project is far from over. Several activities are already underway that will further leverage the latest iteration of the code for a variety of applications:

- WarpX is being applied to the exploration of outstanding questions for plasma-based collider designs on tens of consecutive plasma stages, toward the modeling of multi-TeV high-energy physics colliders based on tens to thousands of plasma-based accelerator stages. Novel algorithms are being studied to improve the accuracy and speed of the code for these studies, including a more versatile and robust implementation of AMR.

- A growing number of users in research labs, academia, and industry are applying WarpX to topics such as laser-ion acceleration, structure-based wakefield acceleration, laser-plasma interaction, plasma instabilities, plasma mirrors, fusion devices, magnetic fusion sheaths, magnetic reconnection, pulsars physics, thermionic converters, electron clouds in accelerators. Several of them are also contributing to the code testing and development.

- The success of WarpX has prompted spinoff projects such as ImpactX, a rewrite of the popular conventional accelerator suite IMPACT (now ImpactX), and HiPACE++, a rewrite of the quasistatic code HiPACE for plasma accelerators. Both have been rewritten for CPUs and GPUs using the AMReX library and sharing data structures and modules with WarpX. Another spinoff is Artemis, which is built on top of WarpX with additional functionalities for the modeling of micromagnetics and electrodynamic waves in next-generation microelectronics.

WarpX was built as a general code with one target application in mind, but it can do much more, and people are already exploring further applications,” Vay said.

Being part of the ECP effort has had a demonstrable impact on this body of research, he added. “The ECP project has been an incredible boost to our scientific code developments and productivity,” he said. “Many of us on the WarpX team agree that it has fostered, between WarpX, AMReX, and partners, the best collaboration experience that we have had to date in our scientific lives. In addition, ECP is enabling us to realize our vision of an integrated PIC ecosystem of codes that is part of a community of integrated scientific software.”

Beyond ECP, more work is now needed to further boost the speed and efficiency of the code, and to address the broad applications in accelerators, fusion, and more. “Make no mistake,” said Vay, “the work on WarpX is not over.” For example, continued work on novel algorithms is needed to improve the accuracy and speed of the code, including a more versatile and robust implementation of AMR.

The ECP WarpX Development Team:

- Ann Almgren (co-PI)

- Arianna Formenti

- Marco Garten

- Kevin Gott

- Junmin Gu

- Axel Huebl

- Revathi Jambunathan

- Hannah Klion

- Prabhat Kumar

- Rémi Lehe

- Andrew Myers

- Ryan Sandberg

- Olga Shapoval

- Maxence Thevenet (now DESY)

- Jean-Luc Vay (PI)

- Weiqun Zhang

- Edoardo Zoni

- David Grote

- Lixin Ge

- Cho Ng

Other contributors from laboratories, universities, and industry in the United States, Europe, and Asia were also involved.

For More Information about WarpX

ECP’s WarpX Team Successfully Models Promising Laser Plasma Accelerator Technology

How AMReX is Influencing the Exascale Landscape

Berkeley Lab-Led WarpX Project Key to 2022 Gordon Bell Prize

About Computing Sciences at Berkeley Lab

High performance computing plays a critical role in scientific discovery. Researchers increasingly rely on advances in computer science, mathematics, computational science, data science, and large-scale computing and networking to increase our understanding of ourselves, our planet, and our universe. Berkeley Lab’s Computing Sciences Area researches, develops, and deploys new foundations, tools, and technologies to meet these needs and to advance research across a broad range of scientific disciplines.

About Computing Sciences at Berkeley Lab

High performance computing plays a critical role in scientific discovery. Researchers increasingly rely on advances in computer science, mathematics, computational science, data science, and large-scale computing and networking to increase our understanding of ourselves, our planet, and our universe. Berkeley Lab's Computing Sciences Area researches, develops, and deploys new foundations, tools, and technologies to meet these needs and to advance research across a broad range of scientific disciplines.