Assessing the Impact of Human-Induced Climate Change

New research finds at least two-thirds of environmental impacts related to recent warming are caused by human emissions of greenhouse gases

December 21, 2015

Contact: Jon Weiner, 510-486-4014, JRWeiner@lbl.gov

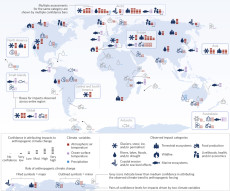

Confidence in attributing observed impacts to regional climate trends, irrespective of the cause for those climate trends. Blue symbols indicate impacts where the observed climate trend has been attributed to anthropogenic forcing with at least medium confidence in a major or minor role. The confidence bars indicate the combined confidence of the impact and climate attribution step. The respective climate driver is indicated by the color of the confidence bars (red, atmospheric air temperature; violet, ocean surface temperature; blue, precipitation). Impacts corresponding to regional climate trends with no, very low or low confidence in attribution to anthropogenic forcing are shown in grey.

This is what scientists know: Human-generated greenhouse gas emissions have contributed to a 1°C (2°F) increase in average global temperature over the last century. Scientists have also observed that rising regional temperatures and altered rainfall are already impacting many of Earth’s glaciers, ecosystems and human communities.

What remains unclear is how much human influence on the climate has actually contributed to these observed regional changes. So Gerrit Hansen of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany and Dáithí Stone of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) in California have developed and applied a methodology for answering this question. Their work was published December 21 in Nature Climate Change.

“A large number of recent studies have revealed that observed climate trends have been impacting a range of ecological, physical, and human systems around the world, but only a handful have demonstrated the relevant climate trend was not just a natural fluctuation,” says Hansen. “We needed to develop a new analysis method that would allow us to fill in this gap.”

She notes that the need to develop this methodology became apparent when she and Stone were tasked with assessing documented evidence of observed climate change impacts for the most recent Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change (IPCC) report.

“The chapter that we worked on listed over one hundred observed climate change impacts,” says Stone. “For our study, we took all of the impacts listed in the IPCC chapter and analyzed the underlying literature in order to determine the relevant region and season for each impact and the corresponding climate driver.”

The duo then analyzed each regional climate trend to determine whether human-generated greenhouse gas emissions were mostly responsible for it.

“We used established analysis procedures to compare the observed climate trends against simulations of models of the climate system describing what should have happened because of our emissions, and against simulations describing what should have happened in the absence of those emissions,” says Stone. Moreover, their approach also considered additional factors, like the quality of climate monitoring, as an integral part of the analysis. They could then assess the overall confidence in their findings, the first time that this has been done for such a large and diverse collection of impacts.

This analysis revealed that almost two-thirds of the listed impacts related to warming over land and at the ocean surface can confidently be attributed to human-generated emissions. However, the same could not be said for related trends in precipitation.

According to Stone, cases where the link between human-generated greenhouse gas emissions and local warming trends was weak were often due to the fact that climate monitoring was insufficient in those regions to build a clear picture about what has been happening over the past several decades.

“In these cases emissions may indeed be driving the warming, we just do not have the data available to confirm it,” says Stone. “You cannot know if something is happening if you are not looking.”

“Studies linking emissions to climate change impacts provide the most stringent test available for evaluating the accuracy of our projections of impacts in a future warmer world. With these tests, we can be much more confident in our calculations of how a 4°C world will differ from a 1.5°C world,” says Wolfgang Cramer, Director of the Mediterranean Institute for Marine and Terrestrial Biodiversity and Ecology in Aix-en-Provence, France. “It is crucial that we continue to develop and maintain monitoring efforts around the world in order to continue documenting how the world is responding to our greenhouse emissions, as well as to agreed reductions in those emissions.”

Cramer, who also led the IPCC report chapter on the detection and attribution of climate change impacts, emphasizes that the robust documentation of evidence of human-induced climate change will be vital for advancing international climate policy following the landmark COP21 conference in Paris this month.

Stone and Hansen’s work was partially supported by the Department of Energy’s Office of Science, and the German Ministry of Education and Research.

About Computing Sciences at Berkeley Lab

High performance computing plays a critical role in scientific discovery. Researchers increasingly rely on advances in computer science, mathematics, computational science, data science, and large-scale computing and networking to increase our understanding of ourselves, our planet, and our universe. Berkeley Lab’s Computing Sciences Area researches, develops, and deploys new foundations, tools, and technologies to meet these needs and to advance research across a broad range of scientific disciplines.

Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube